My advice to writers and artists.

keep evolving

push yourself out of your own bounds

invent, explore, plant your heart where it matters most to you, but don’t clench it there, grow, flourish

read, read, read

write, write, write, write, write, write, write

observe, always

observe with your mind as well as your eye

find what inspires you, and be inspired

draw, draw, draw, draw, draw, draw, draw

don’t be afraid to make messes

make your messes into fascinating things

give it your all, give it your best, identify your best and nurture that

love wisely

if you’re not passionate about it, do something else

join a critique group

learn from others

what will be your contribution to humanity, here and now?

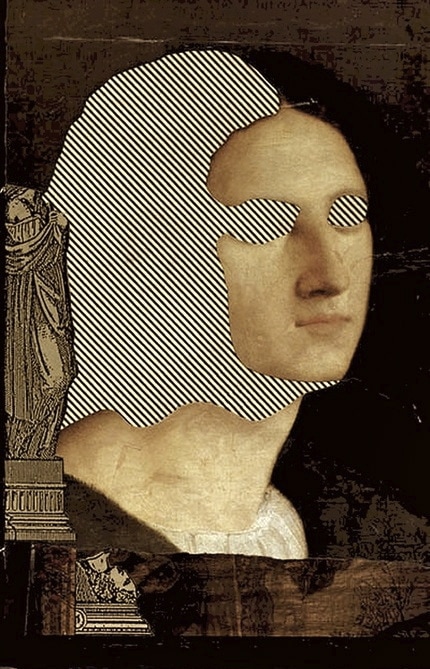

Close the mind and see nothing.

"It's not so much a matter of what we see as it is pondering what we see.

Vision of the mind. This is true for the arts as well as for life itself."

—Troy Howell / collage

The Voices of Children

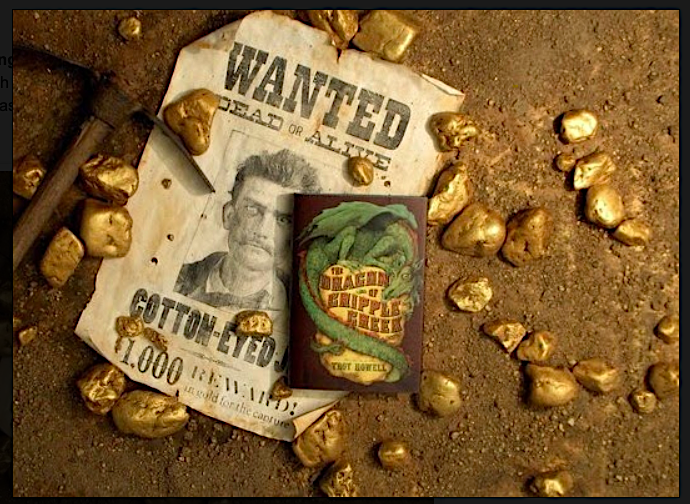

I’m well into another children's book, and as I write I sometimes think of the comments readers have made about my middle grade novel, The Dragon of Cripple Creek (Abrams), which is used in several public school language arts programs. I think about what touched them, worried them, drew them in. It stirs the 12-year-old within me, who jumps up, saying, “Yes! Told you!”

When a group of sixth graders wanted to know how a man my age could have the mind of a 12-year-old, that’s what I told them: The 12-year-old still lives inside me. As does the 18-year-old, and the 24-year-old …

When asked how I could think like a girl (my novel is narrated by 12-year-old Katlin Graham), I answered more thoughtfully, carefully. I have three sisters; I’ve raised a daughter; I listen and observe. While developing the story, I lived the life of Kat, dreamed her dreams. It wasn’t much of a stretch, because a lot of the issues children ponder and face are not gender particular.

But more significant is how the imagination works. No one asked me about getting into the mind of a millennia-old dragon, but he was real enough that my readers didn’t doubt his existence within the confines of the story. Many have cried over him at the end. We humans are gifted with the ability to empathize and identify with other living beings. This gift is given in varying degrees, of course, and equally true, the personal expression of this gift is in varying degrees. It’s one of those essentials that determines whether relationships succeed or fail, or sadly flounder in-between.

The same is true for the writer-reader alliance. The writer must speak words that echo somewhere in the reader's heart, or risk losing connection.

The Dragon of Cripple Creek is on the Accelerated Reader list and some teachers use it in their curriculum. Anticipating my school visits, students sometimes write me letters. Here are a few of their expressions, followed by my related thoughts.

“I find your novel incredibel because it reminds me of my life.”

“Dillon reminds me of myself because we’re both clever and creative.”

We as writers hold up a mirror to our readers, in which they can see themselves, identify more clearly who they are and wish to be. We also hold up a window, through which they can see beyond themselves and understand others.

“I love dragons, wish I could meet one.”

“I also am in love with dragons, so, connection.”

Dreams. Wishes. As a child, I wished I could fly, thought it was possible, wondered what it would feel like. I had seen Peter Pan on TV. I tried with my whole being to fly, leaping off the couch, believing I could soar. When I didn’t succeed, it wasn’t that it was not possible, but that I hadn’t discovered the secret. Conversely, but coming from the same simplicity of faith, I was anxious I’d meet a ghost some quiet afternoon. Interestingly (now that I think of it), my current work in progress features a ghost ... though he's not the type to create much anxiety — that comes from suspense, from threatening circumstances, from fear within the characters that the reader can relate to, accompanied with the precarious hope that all will be well in the end.

“The book had me anxious the whole entire time.”

That’s included in the writer’s intent: to keep the pages turning, the reader engaged, then bring it all together in a satisfying resolve. But it's even more. There's a reason we become anxious, and it's personal: Our own hopes and fears are involved as we read. The final resolve may not be without sadness — usually that is so, if it reflects any reality — but it must offer a feeling of completion. Writers should not disappoint.

“I will tell you the truth I don’t like to read but this is the kind of book I like to read.”

“I really, really hate reading, But …. when I read this its like I don’t wanna stop.”

These are some of the most rewarding expressions a writer can hear. To know you’ve moved someone, perhaps even changed them. It’s one of the wonderful reasons we’re on earth: to give light and joy and receive it in return. When I see a young reader holding my book up and grinning, it’s a reminder of what matters most.

From a third grade teacher:

" I am slowing down my usual pace [of reading aloud] because the kids seem fascinated with Kat's thoughts (which makes me read more expressively). Today we turned out the lights and I read in the semi-darkness as Kat inched closer to the gold. Their expressions were very gratifying. We've completed an hour of read-aloud this week and haven't made it to Chapter 2. I stop for their commentaries — you've provoked a few. "

Fascinated with Kat's thoughts. Why is that? Perhaps it's to see "thinking" at work, to be mindful of critical thought, which helps them process their own.

A few readers have been intrigued by writing itself, with communicating through story:

“I also think you should stick with writing children’s books more.”

“It must take years of practice.”

It does take years of practice, and I’m still practicing.

So I say to all children's writers, and to all of us who make stories for children with our lives: Value their voices. They reveal to us what touches them, puzzles them, frightens, entertains, excites; how they see themselves and others from their own private contexts, within the worlds we’re making. The more we know them, the better we can offer hope, guidance, love. Dare I say that is the primary purpose of what we do? And, not to get too analytical, but the better we can know and love ourselves. I tell that to my 12-year-old self, who says, "Yes. Please."

Listen to the children.

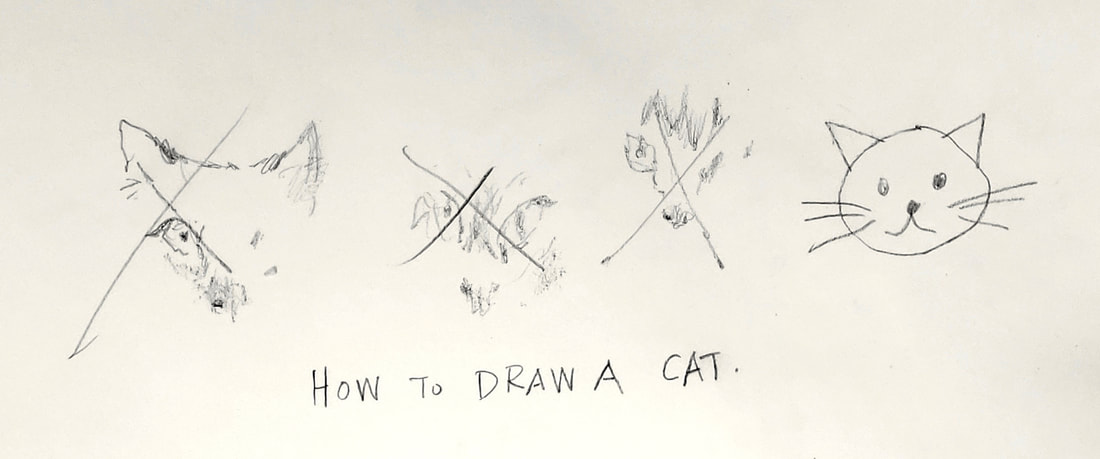

HOW 2 DRAW a CAT (she moved) / pencil, love, effort, haste, abandonment … solution, on paper.

You can try this at home. Be patient with yourself. And if you must, forget the cat.

You can try this at home. Be patient with yourself. And if you must, forget the cat.