I like to analyze what I do. What I’ve done. Why it works. Or why it doesn’t.

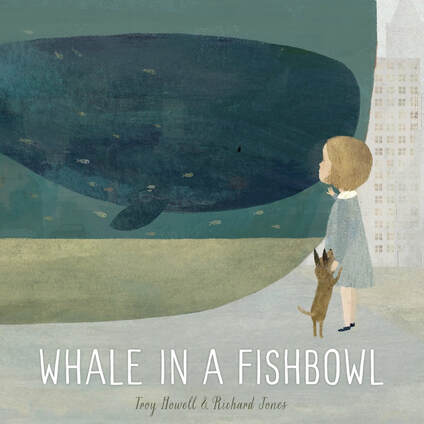

Wednesday is the whale in my picture book, Whale in a Fishbowl. The story won the Golden Kite Honor award from the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, the Northern Lights Book Award, has received starred reviews from four major reviewers, was Amazon's "Best of the Month" selection, and has been published in six countries, so it works for a lot of people.

I want to reach my audience in the best way possible, putting something of value in their hands and hearts and minds. So I’ve been looking at Wednesday in order to help me with other stories I’m working on, and to share my process with fellow writers.

I’ll first say what doesn’t work for me with Wednesday, and I speak only as a writer, not a marketeer. It’s the title. It’s utilitarian. There’s nothing poetic or lyrical about it. Had I gone with only my natural creative mind, I would have called it Wednesday’s Leap, which, in my view, is literary and appealing.

But in this world where marketing is necessary, Whale in a Fishbowl makes sense. Why? It’s immediate. We know right away what the problem is. It gets us thinking, asking questions. On seeing the title alone, we probably have an opinion, even a feeling. Without having read the story yet, we may already have empathy for a whale who is trapped.

That’s what works. The main character is in an impossible situation. And though the title is not the plot (Wednesday’s Leap is closer to that), it sets the stage, the anticipation, for the plot.

As the story progresses, we learn that Wednesday doesn’t know she is trapped. When she’s drawn to the blue in the distance, which everyone knows is the sea (everyone but Wednesday) we’re rooting for her. Like the girl Piper, we want her to know that’s the sea she craves, and that’s where she belongs. We want her to be free.

Another element that works is a twist before the climax. Before her final leap, Wednesday sees only gray (which we know is fog or smog). This adds an unexpected setback. We expect her to see the blue, as before. But this complication makes her try even harder. It raises the stakes. It raises the emotion within her and hopefully within the reader. She is on the verge of giving up, but will try one final time. If the blue isn’t there, she’ll leap no more, resign herself to her static existence. Also, she does not actually see the blue until she’s heading toward it, plunging in. That’s both faith and consequence.

It’s rare for a title to reveal the story problem or the plot, but here are more examples. Robert McCloskey’s Make Way for Ducklings states the plot, plain and gentle. On seeing the title, we know the ducklings need to get from here to there. (Though the storyline's much more involved.) With H. A. Rey’s Curious George the problem is inherent in the mischievous monkey’s name. Well done, for an author who has fun with names. His own, for instance.

In one stroke, Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express tells us everything but who done it and why. The Spy Who Came in From the Cold cloaks the plot in simple yet literary terms, while staying true to the nature of the subject by making use of the Cold War metaphor. (A fascinating aside: The term “cold war” was first used by George Orwell at the end of WW2 to describe the shadow of nuclear threat between the Soviet Union and the West, and “tepid war” appeared in the fourteenth-century writings of Don Juan Manuel, describing the conflict between Christianity and Islam.) Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped captures it in one word. But until we read it, that’s all we know. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest presents the plot in an appropriately cryptic, if not psychotic, way. It’s a beautifully symbolic choice, and is actually taken from a children’s jump-rope rhyme.

Vintery, mintery, cutery, corn,

Apple seed and apple thorn,

Wire, briar, limber lock.

Three geese in a flock.

One flew east,

One flew west,

And one flew over the cuckoo's nest.

Here’s one more, a movie title. Saving Private Ryan tells us the plot in simple terms, and gets us asking: Who is Private Ryan? Why must he be saved? And later, Is he worth it? All compelling reasons to watch the film.

A word of caution for my writer friends. Stating the situation in the title is not usually the best choice to make. It depends on a number of factors: genre, tone, pacing, world building, character development, theme. The Wind in the Willows, for example, creates the lovely, dreamlike tone it’s known for, while giving us its natural setting. The Adventures of Mole, Rat, Badger, and Toad would not have accomplished that.

What's important is that the sooner you reveal the main problem, what the protagonist wants, and what’s at stake, the better your chance of engaging the reader. The sooner they care, the more willing they’ll be to spend time (and money) on what you’re offering. Above all, make it more than worth it. Make it a gift.

To read more about Whale in a Fishbowl, please go here.

Whale in a Fishbowl art by Richard Jones / One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest cover design by Paul Bacon / Make Way for Ducklings art by Robert McCloskey

RSS Feed

RSS Feed