Sometimes the profound takes place in our lives. We have an epiphany or encounter that eclipses all we thought we knew, or had lived, until then. We think we know something or someone until a shift occurs that changes our whole perception. And what may be considered at first an obstruction can reveal a secret or truth that we see now as an opening, an awakening, and we perceive a part of us has been asleep. We wonder what other parts of us are yet to waken. I’ve had such encounters, each involving love and relationship, both human and divine.

I thought I knew the sky, daylight, time. I thought I knew the sun and the moon. They’ve lit my way every day and night of my life from birth until now. They are the ever-present essentials, more constant, even, than breathing and heartbeats. Even in their absence — a new moon, an overcast sky — they are present.

I thought I knew the sun until something as common as the moon got in its way. It was then I saw I did not know either one.

I left for Franklin, North Carolina around 4 AM on August 21st, believing the 8-hour trip would be worth it. But though I have a capable imagination, I could not have imagined what I would see in the 2 minutes and 33 seconds of the total solar eclipse. Neither did I know exactly what I would do, but I took pencils and a sketch pad. I was scarcely prepared for sungazing, for I had borrowed a welder’s lens that I later discovered was not dense or dark enough, and it was too late to find the right shade; all supply shops had sold out weeks before.

I use travel time to pray, enjoy my favorite music, and talk myself through current writing projects, in this case a young adult novel and a children's picture book.

Funny, how ideas for stories begin. About a month ago I’d heard on the radio that moles in America are becoming extinct. I hadn’t really been listening—the radio was noise in the background — but I said to myself, How sad. I’ll write a children’s book about a mole. Immediately an idea grew. The reporter then continued with shopping malls that were closing down, and I knew I had misheard. But the idea was on its way. I chose for my character a mole named Erasmus. On finding out from a class-minded butterfly that he is a star-nosed mole (“You are from the underground,” the butterfly tells him. “But stars are heavenly things.”), Erasmus wonders what stars are, and longs to see them. Impossible for a near-blind creature. Or is it?

As I arrive in Franklin, a single main-street type of town, elevation around 2,000, population twice that amount, now temporarily swelled to its edges, folks are waiting in fields and along streets and on rooftops. I know no one, yet we all share this moment. I settle in and also wait.

The sky is spotted with clouds, mostly cirrus, but as the time draws near, as the moon first touches the sun, a mysterious cloud cover grays to a veil, allowing me to look without damaging my eyes. The disc of the moon shifts closer, closer, reshaping the sun into moon-like stop-motion phases, taking its light bit by bit by bit. The cloud curtain shimmers. The sun is so strong, however, even as it becomes a mere sliver, this series of obstructions provides no suitable prologue to what happens next.

Next, I blink, and in that blink the sky has become a strange new place, an otherworldly stage.

I hear myself cry out, feel tears. I am astonished. The sun is no longer the sun, the moon no longer the moon. A huge black featureless mask stares down at me, as I stand here far below, one among a star-stunned audience, and I know this spectacle in the sky will conduct its choreography whether I witness it or not. I do not matter. None of us do. And yet ... The player behind the mask — the sun, if it still is the sun — reveals in a celebratory flash of self-satisfied splendor, a secret kept for this rare intimate dance: it flings rubies and diamonds around the black rim.

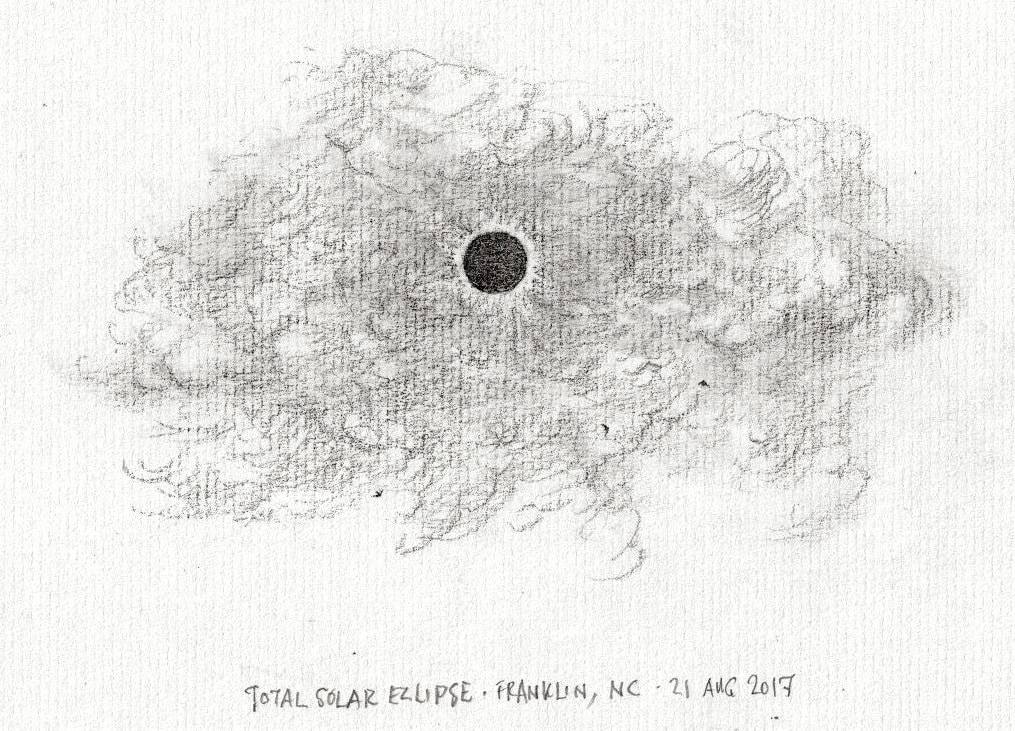

I take my pencil and draw in feeble haste during this timeless yet fleeting moment. A cricket rasps nearby, then becomes reverently still. Tiny swallows glide ecstatically high. It’s impossible to capture the mind-altering magic that is happening on a vast scale in the firmament, impossible with word or line or lens. But I try. We all try. And we know — we who have seen it with our eyes even as we search for comprehension — that at least we have the profound embedded forever within us.

In my children’s story, the lowly mole Erasmus meets a boy, Bootes, who knows all about stars. Bootes promises to show him one up close, something for Erasmus, despite his visual deficiency, to truly see and feel and know. “Meet me in the morning,” says Bootes, and Erasmus is up before dawn, trembling with anticipation. Together they sit in dewy grass, waiting, when the sun rises before them. “There it is,” says Bootes. “Our very own star.” I’m calling the book “Spectacular Things.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed