It probably, very likely, won’t. Believe me. Some things still take work. Lots and lots of work. Unless substance and quality are not important, which is increasingly the case in many areas of life, unfortunately.

Asking an illustrator to get involved will not make it easier and is no shortcut. I’ve had more requests than ever of late to illustrate someone’s children’s book. Requests from people who know next to nothing about the process. (It's replaced the requests to draw their kids.)

The conversation usually goes like this:

Is this a picture book or chapter book or—?

They don’t know.

What’s the word count?

They don’t know.

What’s it about?

The individual is suddenly concerned about copyright.

I explain how copyright works, and offer to take a look at their story and give them advice. More concerns about copyright. I assure them I am not in the business of stealing ideas but coming up with my very own. That once a manuscript is written it’s automatically under copyright …

Manuscript?

You have a manuscript, right?

It’s still in idea form.

Pause for audible silence. I am not a multiple exclamation mark user, since the symbol was designed to emphasize an expression and one serving does the job for me, just as multiple question marks do not make a question any more of a question, but in this case:

So, for all who want to write a children’s book — or any book for that matter — please pay attention. Here are the rules, in order of importance. Break any of them and there will be consequences. You may not recognize it, your dad or your grandkids might not, but there are consequences nonetheless. You don’t know what you don’t know.

Rule one, part one: Go write it. All of it. Got that? All. Of. It. While you’re at it, learn how to write. Then keep learning and learning and learning … Write, write, write, write, write, write, write.

Rule one, part two: Read. Read, not one, not two, but a hundred. Three hundred wouldn’t hurt. Read books written by people who know what they are doing. Read the kind of books you want to write or think you want to write. Find out what makes a story work. How to connect with the reader. Why you are (or if you quit, why you are not), investing your time as a reader with the characters and the story, all the while analyzing why any reader should invest his time with your characters and your story. Learn what showing versus telling means. Plot and structure. Conflict. Voice, point of view. Dialogue. Tone.

Rule two: Go back and rewrite your story. Many, many times. Until it’s the absolute best you can get it. Don’t even think pictures, unless it’s for the purpose of getting your story down and you’re a visual thinker.

Rule three: Join a writer’s critique group. Have them critique it.

Rule four: Go rewrite it again.

Keep doing this so you begin to know about writing, learning from your mistakes and observations, learning from others, and you have a body of work that tells you what you are actually doing and why you are truly doing it. That you are serious about this.

NOW, you can think about getting it published.

Illustrations? Your story must stand on its own. If it does, it will be worthy of illustrations. If, in fact, it needs them.

That’s the bare-bones version.

I encourage writing. I encourage learning to write. I encourage writing and writing and writing. I discourage writing one story and — voilà! — publishing it.

I also suggest doing your homework. Information is so readily available these days there’s no excuse not to be informed. Below are a few links to get you started.

And I do understand. You’re searching through a dream you have only a glimpse of. I wish you all the best.

One more thing: If there's no joy involved, don't trouble yourself.

Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators

The Purple Crayon (Harold Underdown)

KidLit 411

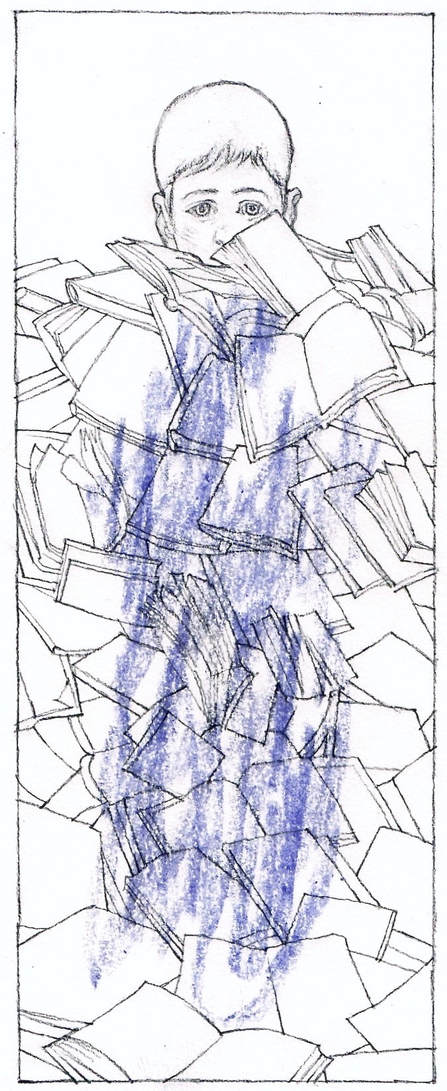

4B pencil & Crayola crayon on Canson mix media paper © 2018 by Troy Howell

RSS Feed

RSS Feed