Now and then I’m asked what my first creative influences were, and I trace a significant one to a moment that shimmers in my childhood. I was eight, sitting enraptured for 34 minutes as I watched a film called The Red Balloon. This singular work sparked something in me I had no definition for but welcomed with all my heart. Captivating my vision like the story's balloon itself, its magic-infused realism showed me there are elements both within and beyond self as needful as breath.

The story is an allegory, played out on Paris streets* by six-year-old Pascal (the filmmaker Albert Lamorisse’s son), who frees a red balloon that’s caught on a lamppost. Together, boy and balloon share the joys of companionship, the challenges of separation, rejection, escape, and finally, death and rebirth.

This simple urban fairy tale — one of the earliest of its genre — captures basic desires of humanity. As we seek acceptance, purpose, gladness, we also hide at times, stumble, dash or press through constricting passages by twists and turns, run up steps, run down, all the while hoping to soar, ultimately, into a lasting place of peace.

Yet there is also that portion of humanity too vast and common that disdains things beautiful and pure, that seeks in ways both physical and psychological to destroy what it neither understands nor possesses (which, I believe, is at the core of the foolish and bitter responses). In the film these are the masses, adults and children alike, who, at the least, display annoyance and indifference, and at the worst, mindless insensibility and harm. The result must ever be: death of the innocent, death by stoning. In the film, time stands still in silent horror at the withering of Pascal’s spirit friend.

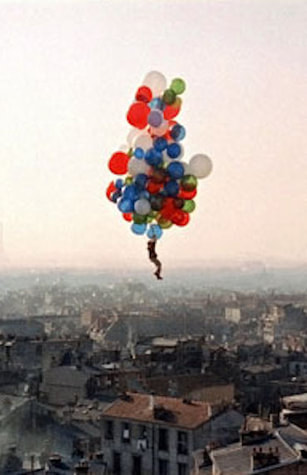

There is, however, a jubilant end to the tale, as a teeming cluster of balloons from all over Paris provides a resurrection. In visionary innocence, Pascal takes hold.

This is what we wish for. For him; perhaps for ourselves.

This is what fantasy realism can do: reveal secrets of the soul. Of life, death, and the spaces in between. Of character, choice, and consequence.

Though not fully comprehending, children yearningly receive.

As I have matured as a writer, I’ve found that almost everything I produce touches back to the glint of raw reality and sparkling truth I saw in The Red Balloon.

* Nearly all of the homes and quarters, cafes and bakeries, steep steps and cobbled lanes among which the story was filmed are gone.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed